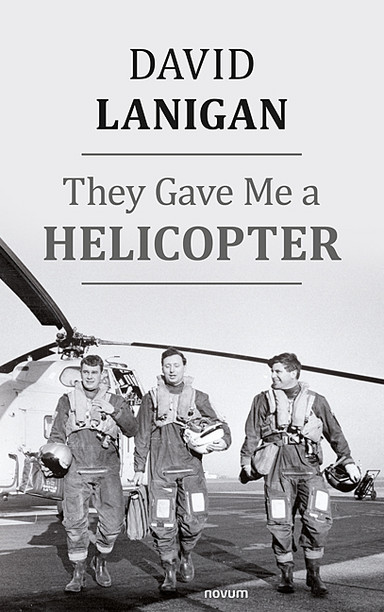

They Gave Me a Helicopter

David Lanigan

USD 30,99

Format: 13.5 x 21.5 cm

Number of Pages: 388

ISBN: 978-3-99131-494-3

Release Date: 13.01.2023

At the age of 12, David Lanigan flew for the first time; They Gave Me A Helicopter is the story of his career in flying, both with the RAF and privately, all over the world. Join David as he learns to fly, builds a family, and never stops learning.

Chapter 4: Final Handling Check

19th December 1962

“Good morning, David. For today’s trip I would like you to plan a low-level cross-country in our local Low Flying Area (LFA). Here is the route. When we have completed that, we will climb up to 25,000 feet for some handling and aerobatics and then return to base.”

Wg. Cdr. Edwards, Chief Flying Instructor (CFI), is briefing me on my Final Handling Check on the Vampire T11 at the end of my advanced jet training course at RAF Valley, Anglesey. It is the 19th December 1962, the end of five months of hectic activity. No time to reflect as I lay out my map, draw in the route, using a sixpence coin to give the right curve at the turning points at 360 knots, 6 miles a minute, a mile every 10 seconds. Ten minutes later the planning is complete, the flight plan written out with the salient leg headings and times scrawled onto my kneepad in chinagraph pencil.

He glances at my flight plan and my map and hands them back. “OK, let’s go.” I stuff the map into my flight suit leg pocket and follow him out to the Dispersal hut. He glances through the Form 700 – the servicing document for our aircraft, XD 445. “The pre-flight inspection has been done, there are no deferred defects, no limitations, and the fuel is full. Let’s go to out to the Line and find our aircraft.”

We leave the hut with our bone domes on, as it is noisy outside, with two ground crew, who will assist us with the start-up and initial taxi. Time for me to start talking.

“When we get to the aircraft I will do an external inspection, starting at the nose and working my way around in a clockwise direction. Then we will climb in, start up, check the brakes, and turn right onto the taxiway towards the threshold of runway 15.”

As we arrive, I start my inspection with the CFI watching and listening. Going round the bulbous plywood nose, I am looking for damage, ducking down to examine the nosewheel for obvious damage, that the tyre is inflated and there are no hydraulic leaks. The engine air intake is clear and there is no sign of foreign object damage. Underneath, the starboard wing all looks normal. The leading edge of the wing looks undamaged. The wing tip is undamaged, as well as the green navigation light. The trailing edge is undamaged and the aileron is secure as well as the flaps, and the airbrake is stowed. The twin booms look normal, tail scrape bulges undamaged, and the elevators are secure. The engine jet pipe looks normal. A minute later the external check is complete, and I climb up the port side, step onto the ejection seat, noting the safety pin is still secure at the back of the seat. The ground crew are helping us to strap in. Firstly the parachute harness, ensuring that we insert the spring clip below the round rotating plate on the quick release box ( QRB) after all straps are locked in . This will prevent premature releasing of the parachute straps should the QRB experience a shock loading during an ejection. Next the ejection seat harness is secured, with its QRB situated above the parachute QRB. When strapped, in the ground crew check that we are happy for the ejection seat safety pins to be taken out and stowed. All secure, I close the canopy, ensuring the lever is in the locked position. On intercom at last, I call out the pre-start checks from memory so that the CFI can both see and hear what I am doing.

Pressing the start button, the engine winds up slowly, and on reaching the minimum rpm I open the High-Pressure Fuel Cock. The engine lights up, does not surge, and accelerates to normal idle rpm. Unlike the Jet Provost I have just trained on, this engine has no acceleration control unit so it is easy to mishandle it, especially at low RPM. All systems working, so more checks on equipment, controls, oxygen, and radios. All is well, so chocks away and calling for taxi on ground frequency using my instructor’s own callsign, 20 Alpha. We are cleared to taxi to the holding point, runway 15. I am marshalled forward, checking the brakes work before we go many yards, then right turn onto the taxiway, acknowledging the help of the ground crew as we set off at walking pace. Once clear of the line we increase the taxi speed and are soon approaching the holding point. On reaching we are directed to tower frequency and request line up and take off. We are cleared to line up but must change to approach frequency for take-off.

As we move onto the runway I complete the pre-take-off checks, turning on the noisy, hot pressurisation, and call, “Approach, 20 Alpha ready for take-off.”

“Clear take-off – climb initially to 3,000 feet on this heading. Call reaching.”

So cleared, I gently open the throttle. When I feel the brakes slipping, I release the brakes and open the throttle fully. I feel the push in the back as we accelerate along the newly resurfaced 9,000-foot runway. 80 knots airspeed, time to lift the nosewheel. A few seconds later the runway drops away; I’m waiting for the airfield boundary before lifting the undercarriage. Three clunks later the three red lights go out and I start the post-take-off checks. Passing 200 feet, our Mk 1 ejection seats will now work effectively. Calling three thousand feet, we are cleared for en-route navigation and set the QHH at 1018, crosschecking altimeters and levelling at 5000 feet heading for the first waypoint – Porthmadog. Soon we are approaching the Welsh coast in the vicinity of Caernarvon and the boundary of the LFA. More checks then, setting the airspeed at 360 knots, we begin a rapid descent to below 500 feet above the ground, but not going below 200 feet – difficult to assess as there is no radio altimeter, so it’s the Mk1 eyeball for that judgement. The weather is fine, good 20-mile visibility, and cloud just on the peaks of the high mountains. If we get trapped below cloud going into a valley, it’s full power and a steep climb to minimum 5,500 feet to ensure clearance of all mountain tops. There are enough crashed aircraft wrecks in the mountains, as evidence of past misjudgements. The countryside is flashing by in a blur, the sheep are not scattering because they don’t hear us coming. I adjust the elevator trim so if I relax on the stick the nose comes up automatically. I can see the first waypoint, Porthmadog. When I reach it, I will turn onto a new heading for Dolgellau and start the stopwatch. Overhead. 60 degrees bank, turning onto next heading, starting the watch. So far so good. Don’t relax. Keep focussed.

We are barrelling along across lumpy country. I can see Dolgellau in the distance, so set the heading marker for the next leg on the compass, ready for the turn. Overhead. Steep turn onto heading, pick a spot on the horizon straight ahead and keeping heading for it. When steady – quick glance at the Ts & Ps. All is well. The lake is coming into view and the waypoint – Llanwddy – is there slightly right of nose, so turn gently towards it. I can see the town and the dam clearly now, so turn in the overhead for Bala. All the time my head is turning left and right, looking out for low flying aircraft, helicopters, and birds. The big reservoir is coming into view, and I need the eastern end of it. Got it, turning on, seconds to go. On course, on speed. Good. Overhead the dam, turning left. On the new heading, I can see mountains on the horizon – Snowdonia. Familiar ground. Next waypoint, Betws y Coed. Did stretcher lowering over a cliff edge there with the mountain rescue team, but no time to identify the spot. There is the little town nestling in the valley with the main road – the A5 – snaking through it. I can see the famous Falls as we come overhead, turning below high ground on the right heading for Capel Curig, with its climbing centres and Outward Bound School.

We are flying along the A5 valley, between high ground, and need to turn early and lift up over high ground on track. After we pass Capel Curig, the distinct wedge shape of Tryfan mountain comes into view; I can see Lyn Ogwen coming up on the nose. Luckily, I did this last week with my instructor, so as we reach the lakeshore I roll on 60 degrees of right bank and pull 2G for five seconds to get us round the corner. This is the exit route from the LFA. Rolling level, we are pointing down a wide valley with the town of Bethesda at the end. Time for a sharp exit from the LFA. Full power and, selecting 15 degrees, nose up. I can see the huge hole in the ground on the left, a former slate mine, as the ground quickly drops away and we are climbing up towards the clouds.

“Valley Approach 20 Alpha climbing to Flight Level 250 overhead the Menai Straights for General Handling.”

“Copied – QNH 1018, weather state Green, runway 15, left hand (circuits) surface wind 180/ 15.”

“Copied.”

As we climb, ice starts to form on the rear of the canopy, in spite of full heat being selected on the pressurisation system. After fifteen minutes at altitude only a small patch on windscreen remains clear, so flying on instruments becomes necessary. Approaching 25,000 feet, time for the pre-aerobatic Hassell checks. I run through them, ending with lookout – so a steep turn to check the skies are clear and we have a distinct horizon for use as a visual reference when recovering from manoeuvres. First, stalls and recovery, clean, then with gear and flaps down. Recovery to the climb. No surprises. Then some spins, first to the left. I still can’t get used to the rapid entry as I pull back on the stick and push the left rudder pedal fully forward. Within a second, we are whirling around, nose down, and with 45 degrees of bank.

“Recover.”

I push the right rudder pedal forward and progressively push the stick forward. With a lurch we stop spinning, I centralise the controls, and we are now in a steep dive. I look for the horizon, level the wings and, checking the airspeed is increasing, gently pull out of the dive and recover to the climb. We have lost three thousand feet in seconds. Our minimum altitude to eject if we can’t recover is 10,000 feet; we are sitting on Mark 1 Martin Baker seats, after all. These aircraft were first flown without ejector seats, a sobering thought.

After a spin to the right and recovery, some aerobatics, starting with loops. Another good look round, then full power nose down, required airspeed, a 2G pull and up we come. As we go over the top, slacken off the G to prevent stalling, and as the nose goes down, reapply. Pointing straight down I recognise Caernarvon Castle between the clouds, confirming we are staying in the local area. Straight into another loop and then some barrel rolls. Then we need to climb to 30,000 feet to experience flight at high Mach numbers. A good look round again, temperatures and pressures are normal, fuel is down to half full – sufficient. Luckily, I did this exercise with my instructor this morning, so I am mentally prepared. It takes a long time to reach the required height; the D.H Goblin centrifugal engine, reliable though it is, is low on thrust at altitude, so patience is required. Eventually we get there, another all-round look out then, heading away from the sun, we enter a steep dive at full throttle. Slowly the airspeed and Mach No build up. Then, around Mach 0.8, the effects of shock waves generated over the wings make their presence felt. The aircraft is shaking, rocking, and pitching uncontrollably; the controls are ineffective. It is unpleasant.

“Recover.”

I throttle back and gently pull back on the stick, we are in a steep dive after all. Suddenly, all is well. The Mach No has dropped as we enter warmer air and although the airspeed is high, we can recover normally to a climb. This aircraft was designed during the war, when there was little understanding of the effects of high speed at altitude. It must have been an unpleasant shock for fighter pilots when they lost control, or worse still, experienced control reversal.

“While we are here, we can look at max rate turns, the first one to the left – keep turning until I give you a roll out heading.”

Setting full power at 250 knots, I pull into a 60-degree banked turn and pull G until I feel a gentle buffet as we are getting close to stalling. There is more drag as we pull G, so the speed drops and I ease the G and angle of bank to keep height. Eventually the situation stabilises at 200 knots and 30 degrees of bank, just nibbling at the buffet – good stall warning.

“Roll out on 360 and climb to 25,000 feet again and we will look at Tail Slides,” (or Hammerhead Stalls).

A few days ago, I practiced these with my instructor, so I am ready and know what to expect. Another good look around, all clear, nose down, full power, I want 250 knots before pulling up into the vertical. I look out sideways at the horizon, making small adjustments to keep going straight up. The airspeed reduces quickly and dropping to 50 means we are now sliding down backwards. Holding all the controls central, I start counting. One, two, three. We lurch over backwards, and for a few seconds fishtail as our vertical descent straightens out. Watching the airspeed, I need 120 knots before levelling the wings with the horizon and pulling out of the dive, initially only gently, looking out for the buffet should we approach the stall. Within seconds we are climbing back up to 25,000 feet. Looking over the side I can see the Menai Straights, so we are still in our local area. A check on Ts & Ps and fuel; down to one third, so must be returning to base shortly. I was not expecting that.

As we level, “Practice engine failure.” My instructor closes the throttle and I need to push the nose down to prevent a stall. I also need to turn towards base somewhere on our right.

“Valley Approach, 20 Alpha, practice engine failure, request homing and let down.”

“All copied, make your heading 290, call passing 20,000 feet.”

“Assume you can’t restart the engine on the way down. I want you to make a glide approach and landing.”

“Valley Approach 20 Alpha passing 20,000 feet, 2 souls on board, request descent in the overhead for glide approach and landing.”

“20 Alpha set QNH 1018, weather 4 eights at 8000 feet, runway 15, left hand, surface wind 180/20 knots. You will be cleared for descent in the overhead, call visual with the field.” With things settled I check Ts & Ps, the engine is at idle rpm (so I can only open the throttle slowly if needed), fuel is one quarter full, so enough for an approach and one circuit if required.

In the overhead, above broken cloud, I can make out the coast but not yet the airfield. With the circuit being left hand I need to circle to the left. Need to conserve energy, height, and speed, and need to stay close to the airfield. We are descending like a streamlined brick towards broken cloud. For a successful approach and landing I need to achieve “high key,” starting the downwind leg at 4,000 feet, and “low key,” turning onto finals at 2,000 feet. Emerging from broken cloud with 300 knots I am too close to the airfield to make an immediate approach to the runway in use, but I have sufficient height and speed to join on the dead side at 6,000 feet plus. I can see the airfield clearly now under the port wing. That will be plan A, trading speed and height for the distance to the start of the downwind leg. Decision is made for me, good. Quick check, engine is still running at idle, there if needed, reassuring. Concentrate now on getting the required parameters of position, height, and airspeed.

Looking good as I call, “20 Alpha visual with the field.”

“QSY tower.”

“Valley tower, 20 Alpha, request join dead side 6,000 feet for glide landing.” Clear join, one in, downwind for full stop landing, set QFE 1016, call downwind. 30 seconds later, “20 Alpha downwind, high for full stop landing.”

“Clear to final, one clearing the runway.”

Pre-landing checks, but undercarriage staying up, flaps remaining up, QFE set at 1016 descending through 3,800 feet, crosscheck, harness check secure. Abeam the runway threshold, height passing 2,000 feet, time to turn onto finals and reduce airspeed to 200 knots, aiming to be lined up with the runway at 1,000 feet. We are high so would land long, so undercarriage is selected down, three clunks, three green lights.

“20 Alpha finals, three greens.”

“20 Alpha, clear land, one joining.”

Still very high, so selecting half flap and adjust the trim. After a few seconds we are still very high, so full flap, the nose dips, and I trim back. I want to land about 1,000 feet into the runway so dive for the threshold at limiting airspeed for the flaps. At 200 feet I begin the round out as we are descending fast. The airspeed reduces immediately. I am aiming for 105 knots at 50 feet above the runway centreline. Normal touch down abeam the 1,000 foot marker, good.

We are slowing down quickly, so gently open the throttle to keep the speed up; we have several thousand feet to go before we can vacate the runway and there is an aircraft calling downwind. Turning off we come to a stop; post-landing checks; pressurisation off, the last of the canopy ice clings on but I can see well enough. All checks OK, and on ground frequency we are cleared back to the line. Fast taxi back to the yellow line at the entrance to the line, then braking to walking pace we are marshalled back to our slot. Handbrake on, chocks in, we can shut down and open the canopy. The ground crew insert the ejector seat face blind pins so that we are safe to get out.

Still pumped up with adrenaline, I greet my instructor as he comes around the nose. “No sign of obvious damage, no obvious oil leaks, no unserviceabilities.”

“Right, I will sign in, then debrief.” The CFI signs the authorisation sheet – 55 minutes, duty carried out. “Right David, that FHT is satisfactory. You will be going on to the Valiant OCU early next month. You will recall that to get you through in time we had to tailor your course, we chopped your formation flying and some general handling. We gave you two, sometimes three flights a day. That good continuity showed today. Some of your colleagues will not be going to their OCUs until March or April, so they are being held back. Your instructor F/O Wells will want to debrief you now. Congratulations.”

I manage a smile, “satisfactory” is all I want to hear.

Postscript:

“White with one sugar, I believe.” My flying instructor, F/O Wells waves me down to a seat in the crew room and pushes a mug of coffee in my direction. “How did it go, any surprises?”

I get out the map and show him the route and the planning. He wants to keep them (could be useful for other students, I’m thinking). We run through the exercises that the CFI had lined up and what I did. Luckily, I had done them all with him in recent days, so I was well up to speed. I knew the parameters that were required, and I was able to produce them to order. He seems very keen to hear of my experiences – was I his first student? He seems very pleased that I had satisfied the CFI. Was I the first of our course to do a Final Handling Check? The good result is going down well with the instructors and my colleagues, so smiles all round.

The Squadron CO comes in and shakes my hand. “Lanigan, your course is finished, report to OC Admin this afternoon, and collect your Clearance Chit. With luck you will be off the Station within a few days and you will get Christmas at home. Some of your colleagues may be here still in April.”

I could hardly say then that I had enjoyed the course, the enthusiasm, the aerobatics and the low flying. The Vampire T11 was certainly robust, I never did tail slides in any other aircraft before or since. In the hectic few months at Valley, I had completed the course, spent weekends in Snowdonia with the Station Mountain Rescue Team, passed my driving test in Holyhead and got engaged. I talk to my instructor about his conversion next year onto the Folland Gnat, which had been designed for our course. I explain that I had been to the factory at Hamble in August and met the workers on the production line. They were struggling with the number of modifications that the RAF were requiring to be incorporated on the production line. They seemed pleased to see me and I was amazed how small the aircraft was. It would be some years before I got a flight on one of them.

As a parting shot, my instructor warned, “In the air what matters is skill, knowledge, experience, and discipline. Good luck.”

I complete the Valiant OCU in April 1963. On debriefing the course, the Station Commander presents me with a letter from Valley, saying that now all students had completed the course, they were awarding the prizes, and I had secured two – for my flying and my ground studies.

Little did I expect that I would be coming back to Valley a few years later to train as a helicopter pilot, as the Valiants I had flown were being chopped up for scrap on the orders of the then Prime Minister – Mr Harold Wilson. My future was now to be operating at low level over land and sea. No more aerobatics at altitude, no more strapping into ejection seats, no more oxygen masks or pressurisation. The future was going to be operating below 10,000 feet often close to the surface, land or sea, in all weathers, by day and by night.

19th December 1962

“Good morning, David. For today’s trip I would like you to plan a low-level cross-country in our local Low Flying Area (LFA). Here is the route. When we have completed that, we will climb up to 25,000 feet for some handling and aerobatics and then return to base.”

Wg. Cdr. Edwards, Chief Flying Instructor (CFI), is briefing me on my Final Handling Check on the Vampire T11 at the end of my advanced jet training course at RAF Valley, Anglesey. It is the 19th December 1962, the end of five months of hectic activity. No time to reflect as I lay out my map, draw in the route, using a sixpence coin to give the right curve at the turning points at 360 knots, 6 miles a minute, a mile every 10 seconds. Ten minutes later the planning is complete, the flight plan written out with the salient leg headings and times scrawled onto my kneepad in chinagraph pencil.

He glances at my flight plan and my map and hands them back. “OK, let’s go.” I stuff the map into my flight suit leg pocket and follow him out to the Dispersal hut. He glances through the Form 700 – the servicing document for our aircraft, XD 445. “The pre-flight inspection has been done, there are no deferred defects, no limitations, and the fuel is full. Let’s go to out to the Line and find our aircraft.”

We leave the hut with our bone domes on, as it is noisy outside, with two ground crew, who will assist us with the start-up and initial taxi. Time for me to start talking.

“When we get to the aircraft I will do an external inspection, starting at the nose and working my way around in a clockwise direction. Then we will climb in, start up, check the brakes, and turn right onto the taxiway towards the threshold of runway 15.”

As we arrive, I start my inspection with the CFI watching and listening. Going round the bulbous plywood nose, I am looking for damage, ducking down to examine the nosewheel for obvious damage, that the tyre is inflated and there are no hydraulic leaks. The engine air intake is clear and there is no sign of foreign object damage. Underneath, the starboard wing all looks normal. The leading edge of the wing looks undamaged. The wing tip is undamaged, as well as the green navigation light. The trailing edge is undamaged and the aileron is secure as well as the flaps, and the airbrake is stowed. The twin booms look normal, tail scrape bulges undamaged, and the elevators are secure. The engine jet pipe looks normal. A minute later the external check is complete, and I climb up the port side, step onto the ejection seat, noting the safety pin is still secure at the back of the seat. The ground crew are helping us to strap in. Firstly the parachute harness, ensuring that we insert the spring clip below the round rotating plate on the quick release box ( QRB) after all straps are locked in . This will prevent premature releasing of the parachute straps should the QRB experience a shock loading during an ejection. Next the ejection seat harness is secured, with its QRB situated above the parachute QRB. When strapped, in the ground crew check that we are happy for the ejection seat safety pins to be taken out and stowed. All secure, I close the canopy, ensuring the lever is in the locked position. On intercom at last, I call out the pre-start checks from memory so that the CFI can both see and hear what I am doing.

Pressing the start button, the engine winds up slowly, and on reaching the minimum rpm I open the High-Pressure Fuel Cock. The engine lights up, does not surge, and accelerates to normal idle rpm. Unlike the Jet Provost I have just trained on, this engine has no acceleration control unit so it is easy to mishandle it, especially at low RPM. All systems working, so more checks on equipment, controls, oxygen, and radios. All is well, so chocks away and calling for taxi on ground frequency using my instructor’s own callsign, 20 Alpha. We are cleared to taxi to the holding point, runway 15. I am marshalled forward, checking the brakes work before we go many yards, then right turn onto the taxiway, acknowledging the help of the ground crew as we set off at walking pace. Once clear of the line we increase the taxi speed and are soon approaching the holding point. On reaching we are directed to tower frequency and request line up and take off. We are cleared to line up but must change to approach frequency for take-off.

As we move onto the runway I complete the pre-take-off checks, turning on the noisy, hot pressurisation, and call, “Approach, 20 Alpha ready for take-off.”

“Clear take-off – climb initially to 3,000 feet on this heading. Call reaching.”

So cleared, I gently open the throttle. When I feel the brakes slipping, I release the brakes and open the throttle fully. I feel the push in the back as we accelerate along the newly resurfaced 9,000-foot runway. 80 knots airspeed, time to lift the nosewheel. A few seconds later the runway drops away; I’m waiting for the airfield boundary before lifting the undercarriage. Three clunks later the three red lights go out and I start the post-take-off checks. Passing 200 feet, our Mk 1 ejection seats will now work effectively. Calling three thousand feet, we are cleared for en-route navigation and set the QHH at 1018, crosschecking altimeters and levelling at 5000 feet heading for the first waypoint – Porthmadog. Soon we are approaching the Welsh coast in the vicinity of Caernarvon and the boundary of the LFA. More checks then, setting the airspeed at 360 knots, we begin a rapid descent to below 500 feet above the ground, but not going below 200 feet – difficult to assess as there is no radio altimeter, so it’s the Mk1 eyeball for that judgement. The weather is fine, good 20-mile visibility, and cloud just on the peaks of the high mountains. If we get trapped below cloud going into a valley, it’s full power and a steep climb to minimum 5,500 feet to ensure clearance of all mountain tops. There are enough crashed aircraft wrecks in the mountains, as evidence of past misjudgements. The countryside is flashing by in a blur, the sheep are not scattering because they don’t hear us coming. I adjust the elevator trim so if I relax on the stick the nose comes up automatically. I can see the first waypoint, Porthmadog. When I reach it, I will turn onto a new heading for Dolgellau and start the stopwatch. Overhead. 60 degrees bank, turning onto next heading, starting the watch. So far so good. Don’t relax. Keep focussed.

We are barrelling along across lumpy country. I can see Dolgellau in the distance, so set the heading marker for the next leg on the compass, ready for the turn. Overhead. Steep turn onto heading, pick a spot on the horizon straight ahead and keeping heading for it. When steady – quick glance at the Ts & Ps. All is well. The lake is coming into view and the waypoint – Llanwddy – is there slightly right of nose, so turn gently towards it. I can see the town and the dam clearly now, so turn in the overhead for Bala. All the time my head is turning left and right, looking out for low flying aircraft, helicopters, and birds. The big reservoir is coming into view, and I need the eastern end of it. Got it, turning on, seconds to go. On course, on speed. Good. Overhead the dam, turning left. On the new heading, I can see mountains on the horizon – Snowdonia. Familiar ground. Next waypoint, Betws y Coed. Did stretcher lowering over a cliff edge there with the mountain rescue team, but no time to identify the spot. There is the little town nestling in the valley with the main road – the A5 – snaking through it. I can see the famous Falls as we come overhead, turning below high ground on the right heading for Capel Curig, with its climbing centres and Outward Bound School.

We are flying along the A5 valley, between high ground, and need to turn early and lift up over high ground on track. After we pass Capel Curig, the distinct wedge shape of Tryfan mountain comes into view; I can see Lyn Ogwen coming up on the nose. Luckily, I did this last week with my instructor, so as we reach the lakeshore I roll on 60 degrees of right bank and pull 2G for five seconds to get us round the corner. This is the exit route from the LFA. Rolling level, we are pointing down a wide valley with the town of Bethesda at the end. Time for a sharp exit from the LFA. Full power and, selecting 15 degrees, nose up. I can see the huge hole in the ground on the left, a former slate mine, as the ground quickly drops away and we are climbing up towards the clouds.

“Valley Approach 20 Alpha climbing to Flight Level 250 overhead the Menai Straights for General Handling.”

“Copied – QNH 1018, weather state Green, runway 15, left hand (circuits) surface wind 180/ 15.”

“Copied.”

As we climb, ice starts to form on the rear of the canopy, in spite of full heat being selected on the pressurisation system. After fifteen minutes at altitude only a small patch on windscreen remains clear, so flying on instruments becomes necessary. Approaching 25,000 feet, time for the pre-aerobatic Hassell checks. I run through them, ending with lookout – so a steep turn to check the skies are clear and we have a distinct horizon for use as a visual reference when recovering from manoeuvres. First, stalls and recovery, clean, then with gear and flaps down. Recovery to the climb. No surprises. Then some spins, first to the left. I still can’t get used to the rapid entry as I pull back on the stick and push the left rudder pedal fully forward. Within a second, we are whirling around, nose down, and with 45 degrees of bank.

“Recover.”

I push the right rudder pedal forward and progressively push the stick forward. With a lurch we stop spinning, I centralise the controls, and we are now in a steep dive. I look for the horizon, level the wings and, checking the airspeed is increasing, gently pull out of the dive and recover to the climb. We have lost three thousand feet in seconds. Our minimum altitude to eject if we can’t recover is 10,000 feet; we are sitting on Mark 1 Martin Baker seats, after all. These aircraft were first flown without ejector seats, a sobering thought.

After a spin to the right and recovery, some aerobatics, starting with loops. Another good look round, then full power nose down, required airspeed, a 2G pull and up we come. As we go over the top, slacken off the G to prevent stalling, and as the nose goes down, reapply. Pointing straight down I recognise Caernarvon Castle between the clouds, confirming we are staying in the local area. Straight into another loop and then some barrel rolls. Then we need to climb to 30,000 feet to experience flight at high Mach numbers. A good look round again, temperatures and pressures are normal, fuel is down to half full – sufficient. Luckily, I did this exercise with my instructor this morning, so I am mentally prepared. It takes a long time to reach the required height; the D.H Goblin centrifugal engine, reliable though it is, is low on thrust at altitude, so patience is required. Eventually we get there, another all-round look out then, heading away from the sun, we enter a steep dive at full throttle. Slowly the airspeed and Mach No build up. Then, around Mach 0.8, the effects of shock waves generated over the wings make their presence felt. The aircraft is shaking, rocking, and pitching uncontrollably; the controls are ineffective. It is unpleasant.

“Recover.”

I throttle back and gently pull back on the stick, we are in a steep dive after all. Suddenly, all is well. The Mach No has dropped as we enter warmer air and although the airspeed is high, we can recover normally to a climb. This aircraft was designed during the war, when there was little understanding of the effects of high speed at altitude. It must have been an unpleasant shock for fighter pilots when they lost control, or worse still, experienced control reversal.

“While we are here, we can look at max rate turns, the first one to the left – keep turning until I give you a roll out heading.”

Setting full power at 250 knots, I pull into a 60-degree banked turn and pull G until I feel a gentle buffet as we are getting close to stalling. There is more drag as we pull G, so the speed drops and I ease the G and angle of bank to keep height. Eventually the situation stabilises at 200 knots and 30 degrees of bank, just nibbling at the buffet – good stall warning.

“Roll out on 360 and climb to 25,000 feet again and we will look at Tail Slides,” (or Hammerhead Stalls).

A few days ago, I practiced these with my instructor, so I am ready and know what to expect. Another good look around, all clear, nose down, full power, I want 250 knots before pulling up into the vertical. I look out sideways at the horizon, making small adjustments to keep going straight up. The airspeed reduces quickly and dropping to 50 means we are now sliding down backwards. Holding all the controls central, I start counting. One, two, three. We lurch over backwards, and for a few seconds fishtail as our vertical descent straightens out. Watching the airspeed, I need 120 knots before levelling the wings with the horizon and pulling out of the dive, initially only gently, looking out for the buffet should we approach the stall. Within seconds we are climbing back up to 25,000 feet. Looking over the side I can see the Menai Straights, so we are still in our local area. A check on Ts & Ps and fuel; down to one third, so must be returning to base shortly. I was not expecting that.

As we level, “Practice engine failure.” My instructor closes the throttle and I need to push the nose down to prevent a stall. I also need to turn towards base somewhere on our right.

“Valley Approach, 20 Alpha, practice engine failure, request homing and let down.”

“All copied, make your heading 290, call passing 20,000 feet.”

“Assume you can’t restart the engine on the way down. I want you to make a glide approach and landing.”

“Valley Approach 20 Alpha passing 20,000 feet, 2 souls on board, request descent in the overhead for glide approach and landing.”

“20 Alpha set QNH 1018, weather 4 eights at 8000 feet, runway 15, left hand, surface wind 180/20 knots. You will be cleared for descent in the overhead, call visual with the field.” With things settled I check Ts & Ps, the engine is at idle rpm (so I can only open the throttle slowly if needed), fuel is one quarter full, so enough for an approach and one circuit if required.

In the overhead, above broken cloud, I can make out the coast but not yet the airfield. With the circuit being left hand I need to circle to the left. Need to conserve energy, height, and speed, and need to stay close to the airfield. We are descending like a streamlined brick towards broken cloud. For a successful approach and landing I need to achieve “high key,” starting the downwind leg at 4,000 feet, and “low key,” turning onto finals at 2,000 feet. Emerging from broken cloud with 300 knots I am too close to the airfield to make an immediate approach to the runway in use, but I have sufficient height and speed to join on the dead side at 6,000 feet plus. I can see the airfield clearly now under the port wing. That will be plan A, trading speed and height for the distance to the start of the downwind leg. Decision is made for me, good. Quick check, engine is still running at idle, there if needed, reassuring. Concentrate now on getting the required parameters of position, height, and airspeed.

Looking good as I call, “20 Alpha visual with the field.”

“QSY tower.”

“Valley tower, 20 Alpha, request join dead side 6,000 feet for glide landing.” Clear join, one in, downwind for full stop landing, set QFE 1016, call downwind. 30 seconds later, “20 Alpha downwind, high for full stop landing.”

“Clear to final, one clearing the runway.”

Pre-landing checks, but undercarriage staying up, flaps remaining up, QFE set at 1016 descending through 3,800 feet, crosscheck, harness check secure. Abeam the runway threshold, height passing 2,000 feet, time to turn onto finals and reduce airspeed to 200 knots, aiming to be lined up with the runway at 1,000 feet. We are high so would land long, so undercarriage is selected down, three clunks, three green lights.

“20 Alpha finals, three greens.”

“20 Alpha, clear land, one joining.”

Still very high, so selecting half flap and adjust the trim. After a few seconds we are still very high, so full flap, the nose dips, and I trim back. I want to land about 1,000 feet into the runway so dive for the threshold at limiting airspeed for the flaps. At 200 feet I begin the round out as we are descending fast. The airspeed reduces immediately. I am aiming for 105 knots at 50 feet above the runway centreline. Normal touch down abeam the 1,000 foot marker, good.

We are slowing down quickly, so gently open the throttle to keep the speed up; we have several thousand feet to go before we can vacate the runway and there is an aircraft calling downwind. Turning off we come to a stop; post-landing checks; pressurisation off, the last of the canopy ice clings on but I can see well enough. All checks OK, and on ground frequency we are cleared back to the line. Fast taxi back to the yellow line at the entrance to the line, then braking to walking pace we are marshalled back to our slot. Handbrake on, chocks in, we can shut down and open the canopy. The ground crew insert the ejector seat face blind pins so that we are safe to get out.

Still pumped up with adrenaline, I greet my instructor as he comes around the nose. “No sign of obvious damage, no obvious oil leaks, no unserviceabilities.”

“Right, I will sign in, then debrief.” The CFI signs the authorisation sheet – 55 minutes, duty carried out. “Right David, that FHT is satisfactory. You will be going on to the Valiant OCU early next month. You will recall that to get you through in time we had to tailor your course, we chopped your formation flying and some general handling. We gave you two, sometimes three flights a day. That good continuity showed today. Some of your colleagues will not be going to their OCUs until March or April, so they are being held back. Your instructor F/O Wells will want to debrief you now. Congratulations.”

I manage a smile, “satisfactory” is all I want to hear.

Postscript:

“White with one sugar, I believe.” My flying instructor, F/O Wells waves me down to a seat in the crew room and pushes a mug of coffee in my direction. “How did it go, any surprises?”

I get out the map and show him the route and the planning. He wants to keep them (could be useful for other students, I’m thinking). We run through the exercises that the CFI had lined up and what I did. Luckily, I had done them all with him in recent days, so I was well up to speed. I knew the parameters that were required, and I was able to produce them to order. He seems very keen to hear of my experiences – was I his first student? He seems very pleased that I had satisfied the CFI. Was I the first of our course to do a Final Handling Check? The good result is going down well with the instructors and my colleagues, so smiles all round.

The Squadron CO comes in and shakes my hand. “Lanigan, your course is finished, report to OC Admin this afternoon, and collect your Clearance Chit. With luck you will be off the Station within a few days and you will get Christmas at home. Some of your colleagues may be here still in April.”

I could hardly say then that I had enjoyed the course, the enthusiasm, the aerobatics and the low flying. The Vampire T11 was certainly robust, I never did tail slides in any other aircraft before or since. In the hectic few months at Valley, I had completed the course, spent weekends in Snowdonia with the Station Mountain Rescue Team, passed my driving test in Holyhead and got engaged. I talk to my instructor about his conversion next year onto the Folland Gnat, which had been designed for our course. I explain that I had been to the factory at Hamble in August and met the workers on the production line. They were struggling with the number of modifications that the RAF were requiring to be incorporated on the production line. They seemed pleased to see me and I was amazed how small the aircraft was. It would be some years before I got a flight on one of them.

As a parting shot, my instructor warned, “In the air what matters is skill, knowledge, experience, and discipline. Good luck.”

I complete the Valiant OCU in April 1963. On debriefing the course, the Station Commander presents me with a letter from Valley, saying that now all students had completed the course, they were awarding the prizes, and I had secured two – for my flying and my ground studies.

Little did I expect that I would be coming back to Valley a few years later to train as a helicopter pilot, as the Valiants I had flown were being chopped up for scrap on the orders of the then Prime Minister – Mr Harold Wilson. My future was now to be operating at low level over land and sea. No more aerobatics at altitude, no more strapping into ejection seats, no more oxygen masks or pressurisation. The future was going to be operating below 10,000 feet often close to the surface, land or sea, in all weathers, by day and by night.